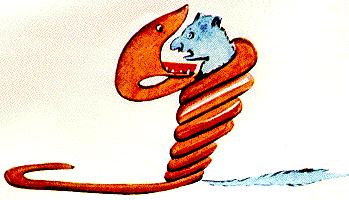

Lorsque j'avais six ans j'ai vu, une fois, une magnifique image, dans un livre sur la Forêt Vierge qui s'appelait "Histoires Vécues". Ça représentait un serpent boa qui avalait un fauve. Voilà la copie du dessin.

On disait dans le livre: "Les serpents boas avalent leur proie tout entière, sans la mâcher. Ensuite ils ne peuvent plus bouger et ils dorment pendant les six mois de leur digestion".

J'ai alors beaucoup réfléchi sur les aventures de la jungle et, à mon tour, j'ai réussi, avec un crayon de couleur, à tracer mon premier dessin. Mon dessin numéro 1. Il était comme ça:

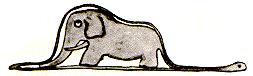

J'ai montré mon chef d'oeuvre aux grandes personnes et je leur ai demandé si mon dessin leur faisait peur.

Elles m'ont répondu: "Pourquoi un chapeau ferait-il peur?"

Mon dessin ne représentait pas un chapeau. Il représentait un serpent boa qui digérait un éléphant. J'ai alors dessiné l'intérieur du serpent boa, afin que les grandes personnes puissent comprendre. Elles ont toujours besoin d'explications. Mon dessin numéro 2 était comme ça:

Les grandes personnes m'ont conseillé de laisser de côté les dessins de serpents boas ouverts ou fermés, et de m'intéresser plutôt à la géographie, à l'histoire, au calcul et à la grammaire. C'est ainsi que j'ai abandonné, à l'âge de six ans, une magnifique carrière de peinture. J'avais été découragé par l'insuccès de mon dessin numéro 1 et de mon dessin numéro 2. Les grandes personnes ne comprennent jamais rien toutes seules, et c'est fatigant, pour les enfants, de toujours leur donner des explications.

J'ai donc dû choisir un autre métier et j'ai appris à piloter des avions. J'ai volé un peu partout dans le monde. Et la géographie, c'est exact, m'a beaucoup servi. Je savais reconnaître, du premier coup d'oeil, la Chine de l'Arizona. C'est utile, si l'on est égaré pendant la nuit.

J'ai ainsi eu, au cours de ma vie, des tas de contacts avec des tas de gens sérieux. J'ai beaucoup vécu chez les grandes personnes. Je les ai vues de très près. Ça n'a pas trop amélioré mon opinion.

Quand j'en rencontrais une qui me paraissait un peu lucide, je faisais l'expérience sur elle de mon dessin no.1 que j'ai toujours conservé. Je voulais savoir si elle était vraiment compréhensive. Mais toujours elle me répondait: "C'est un chapeau." Alors je ne lui parlais ni de serpents boas, ni de forêts vierges, ni d'étoiles. Je me mettais à sa portée. Je lui parlais de bridge, de golf, de politique et de cravates. Et la grande personne était bien contente de connaître un homme aussi raisonnable//

................................................................................................................................

In one of his nastier moods, Sartre accused Camus of writing like Chateaubriand. The essay-portraits of Algiers and Oran, the nostalgic evocations of Camus' Mediterranean background, his buoyant, often dramatized philosophical love affair with nature--these were the parts of Camus' temperament that Sartre found at odds with the prevailing existentialist gloom of the post-war period when he and Camus held an uneasy alliance as spokesmen for their age. Sartre represented a soi-disant authentic anguish ultimately leading to social revolt, Camus the enigma of a passionate man who sought to triumph over the innate absurdity of life. Lyrical and Critical Essays comprises Camus' youthful reflections. L'Envers et l'Endroit; his two brilliant summations of the sensual world. Noces and L'Etc. both of which shed much light on the varying landscapes of his major novels; and his stray reviews (including comments on Sartre's fiction), interviews, and assorted marginalia. These newly translated works are of inestimable importance in reaching some understanding of Campus' personality, his relationship with traditional values, and (to return to Sartre) the qualified Romantic animism in Camus' style and feeling. In a sense, Sartre is right. There is something intellectually equivocal, even hortatory, in Camus' paradoxical celebration of lucidity amid nihilism, participation amid withdrawal. But Camus is more the measure of man and man's physical and spiritual union with the universe, however idealized//

..................................................................................

Camus’ writing style is concise and specific. He doesn’t use excessive amounts of figurative language but, instead, bluntly expresses his characters’ views. The brilliance of Camus’ writing is his ability to adapt his style to reflect the unique personality of the narrator and the specific themes of each novel, with a focus on showing his characters’ detachment. This skill becomes apparent after reading his three works The Plague, The Fall, and The Stranger.

Camus’ straightforward writing is most apparent in his novel The Stranger. The existentialist narrator Meursault allows Camus to exaggerate the direct thoughts of his character. An example of this is Meursault’s simple logic: “I worked hard at the office today. The boss was nice…Before leaving the office to go to lunch, I washed my hands. I really like doing this at lunchtime. I don’t enjoy it so much in the evening, because the roller towel you use is soaked through: one towel has to last all day” (25). His basic sentences reflect his rational thought process. When Meursault recalls the traumatic events of a newspaper article in jail, he uses clear language in both the summary and his reaction: “The mother hanged herself. The sister threw herself down a well…On the one hand it wasn’t very likely. on the other, it was perfectly natural” (80). The writing is basic, yet it highlights Meursault’s detached point of view accurately.

In his other novel, The Plague, Camus uses greater complexity in thought and sentence structure, though detached in another way. While the anonymous narrator clearly expresses his impressions and account of the disease, his commentary is intricate and interesting. For example, while describing a conversation, The Plague’s narrator uses variety in his sentences. He introduces a minor character Raoul with rich imagery: “Again ‘the friend’ slowly moved his equine head up and down, without ceasing to munch the tomato and pimento salad he was shoveling into his mouth” (148). Yet after brief dialogue, Camus reverts back to his basics: “Horse-face nodded slow approval once more. Some time was spent looking for a subject of conversation” (148). The difference of styles in The Plague and The Stranger, as well as in his novel The Fall, shows Camus’ versatility.

A key characteristic of Camus’ writing is his ability to adapt to the needs of a specific novel. In all three of these Camus novels, he adapts his writing style to highlight detachment but changes his language choice and sentence structure to fit the voice of a particular narrator. The Stranger being somewhat of an exception, Camus tends to use an intermediary character, someone that creates a barrier between the reader and the novel. Though there isn’t a character separating Meursault and the reader, his language is so detached from the action of the story that the reader feels a gap form. As previously highlighted, Meursault has a clear and concise manner of thinking. His stark narration implies that he doesn’t feel responsible for his actions. When he shoots a gun, he describes it in passive voice: “The trigger gave,” as if he wasn’t the one who pulled it (59). Yet in his other two novels, The Plague and The Fall, Camus places figurative barriers between the characters and the reader. In these two novels, his style is to frequently remind the reader of their separation.

In The Plague, Camus uses an anonymous character to synthesize the collections of writings and accounts to recount to the reader. The narrator uses language to imply that he was a resident of the town. He comments: “The town itself, let us admit, is ugly” and frequently uses “our” as a reference (3). To remind the reader of the intermediary character, Camus inserts statements like: “if Tarrou’s notes are correct” and later admits after revealing his identity that “he expressly made a point of adopting the tone of an impartial observer,” to imply these are not the opinions of the author and that he tries to use credible sources for his information (275, 301). Camus uses distinct language to present this “unbiased” account and therefore adjusts his style.

In The Fall, the narrator, Jean-Baptiste Clamence, tells his life story to a fellow French expatriate in a bar in Amsterdam called Mexico City; the entire novel is in Clamence’s words. Naturally, Camus changes his style to fit the personality of Clamence and remind the reader of the situation that both Clamence and the unnamed listener are in. He uses questions and implies the answers in the following statements: “Are you staying in Amsterdam? A beautiful city isn’t it? Fascinating? There’s an adjective I haven’t heard in some time” (6). Clamence frequently addresses his listener–his terms for his increase in familiarity throughout the novel. At first, Clamence uses “monsieur,” which eventually becomes “cher monsieur,” which develops into “mon cher compatriote” (3,32,48). The names of endearment continue: “mon ami,” “cher,” and “mon cher” (73,97,111). Other aspects of Camus’ style, such as the grammar, give it a speaking quality. Camus includes many elipses to indicate a natural pause in Clamence’s long speech: “And yet…You see,cher monsieur” (37). The last lines of the novel are exclamations to show Clamence’s passion: “Brrr..! The water’s so cold! But let’s not worry. It’s too late now. It will always be too late. Fortunately!” (147). Camus carefully and deliberately adjusts his grammar, word choice, and overall style of the narration to emphasize the separation between the reader and the main characters.

Within Camus’ writing, there are many differences, such as point of view, sentence complexity, and overall style. Yet the concise and lucid sentences along with a clear intention to detach reader and character connect and unify his works.

'영문원고' 카테고리의 다른 글

| rv hosteller 6-s journey for journey (0) | 2015.11.12 |

|---|---|

| rv hosteler 6-3 Paris (0) | 2015.11.10 |

| rv hosteller 6-1 Paris experience (0) | 2015.11.09 |

| rv hosteler 10-1 Atlanta (0) | 2015.11.04 |

| rv hosteller 11-1 Spain (0) | 2015.11.03 |